The scenario is inevitable, more predictable than the weather event it follows. A line of severe thunderstorms bullies the Tennessee Valley. Television weather teams mobilize, in studio and on the roads, holding the audience's hand until danger has passed. It's live television, the most intimate news source.

But the next day, the same weather images are back -- clipped and tidied into a commercial, with musical backbeat and colorful, spiraling graphics. "Exclusive!" the narrator touts. "WE brought it to you FIRST. And we covered it BEST." The pitch extends into technological ballyhoo -- storm trackers and Doppler radars. Then the kicker -- lives saved, a community sheltered from the storm.

In television circles, this is called a "pop," as in Proof of Performance. A news station covers an event, then it lets you know how good a job it did. The television news doesn't just come as news anymore. It comes back at you to cover how the station covered the story, and how fast, and with what technology.

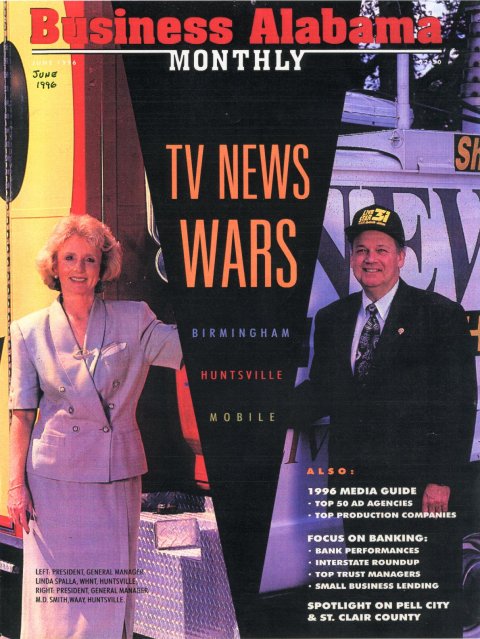

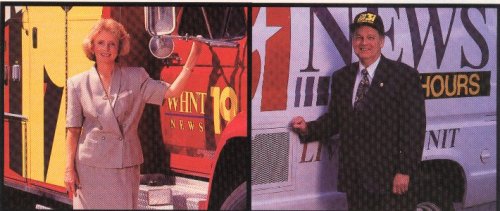

It would be hard to imagine -- and harder to wish for -- a more extreme example of this phenomenon of modern teleivison biz than in North Alabama. Here in the Tennessee Valley market leaders WHNT- Channel 19 and WAAY-Channel 31 have been waging a ratings war with satellite trucks and choppers and mobile weather units. Viewers have been pinned down with a veritable box barrage of "pops" peppered throughout programming, including salvos of self-promotion during the newscasts themselves.

The two stations cover 12 counties surrounding Huntsville, including two in Tennessee. For years, WAAY had been the ratings leader with WHNT and WAFF-Channel 48 following. But in the most recently published ratings books, WHNT -- with a glossy new look and avid promotional campaign -- surged ahead. For the sweeps period in February Nielson surveys showed WHNT with a 31 percent share of the 6 PM news compared to WAAY's 24 percent share and WAFF's 10 percent. During the 10 PM news slot, WHNT garnered 34 percent to WAAY's 25 percent share and WAFF's 12 percent share.

For recently dethroned leader WAAY, it's been -- in the words of a golden-age comedian -- a revolting development. The turn-about provoked a WAAY promotional push of its own, and an escalation of the ratings race.

It's a struggle between the comfortable, family-owned station, WAAY, and the New York times upstart, WHNT. But now the news comes with ridicule following close behind. A former competing general manager has called the two stations "laughing stocks." Letters have been written calling the competition "silly." Calls have been placed to call-in lines saying much worse. They wonder, 'Is the local TV battle just part of everyday commerce, except with businesses that have a great deal of public resources? Or does the race for ratings have all the integrity of two teens showing off their cars on Saturday night?'

These are the questions Huntsville viewers are asking. How far, they wonder, is too far in television news?

OLD VS. NEW

A little too far. That's what M.D. Smith says. The WAAY president and general manager has no surveys that say he's right, no charts to verify his conviction. He just has 32 years of watching the Tennessee Valley from his office on Monte Sano, high atop Huntsville, just as his kinfolk in business have done before him.

"There's a point where you can't be any louder," he says. "I've judged my competition to be more of that (loud) than they used to be, and we're not going to be."

Too far? Linda Spalla doesn't agree. Every day, WHNT's president and general manager watches broadcasts on the three televisions in her office, and she says she sees no three-ring circus -- in fact, nothing more unseemly than free enterprise and the American way.

"I'm almost amazed at how much people resent how hard we try to get ratings," Spalla says. "When Parisian has a bargain days sale, theypull out all the stops. It's the same for us in ratings points. It is truly a private business.

"We know it's a business where we're not going to please everyone. But we get so much positive feedback from our viewers."

At WAFF-Channel 48, the perennial third-place station in Huntsville, new general manager Mark Pimental says he has stayed out of the promotion fray on purpose while he beefs up his staff. But he realizes he can hardly afford to remain out.

"I think as 1996 progresses, you will see us reemerge into promotional venues," he says. "But I wouldn't say we're going to do it on the level of the other stations."

Everyone agrees that, as with most businesses, self-promotion is a must. Study upon study has shown that viewers decide what they want to watch by watching. More promotion yields better ratings, which yield higher ad rates and significantly higher revenues.

When local television news programs are in the tangle of competition, promotion becomes even more critical, since they command premium advertising rates. In Huntsville, that battle began about 3 1/2 years ago. In fact, Spalla says she can almost put her finger on the date WHNT began what she calls a "new commitment" to improving its newscast and weather coverage. The station hired a new director of news, and it put a greater focus on local news and weather.

"It was all a package," Spalla says, "and promotion was a part of that."

Smith's reaction to that campaign was obligatory, he says, certainly nothing for which to apologize. "When a station is doing a 'pop,' it's letting the viewers know how it covered something," he says, "If one station did this and the other two didn't, people might think, 'Well, the other two didn't do as much.'"

The same rationale holds for satellite trucks and helicopters and weather technology. If new purchases are improving the product, Smith says, why make it a secret?

Some consumers, however, are asking another question: "What's the difference between hype and legitimate news?"

It's a matter of tone, Smith says. When a news station syas its weather technology will give people better warning of severe weather, that's legitimate news. But when a station attaches too much meaning to that better warning, that's when the problems begin.

"It's how much you say," Smith argues. "If you say, 'This is the greatest thing in the valley. It will save thousands of lives,' that's when you cross the line."

"I think the audience is wise enough to see through some of it," says WAFF's Pimental. "But not all of it."

WEATHER WARS

In a market such as Huntsville, where tornadoes threaten with unnerving frequency, weather coverage and all the attendant technology tends to be the eye of the promotions storm.

In Huntsville everyone has a tornado story. Smith tells of the first big one, the 1974 tornado, the one that first grabbed Huntsville by the lapels. Huddled with his children in the below- ground workshop of his house, he recalls hearing the roar of the tornado as it passed over nearby Parkway City Mall, then over the top of his house. "I got a pretty good feeling about what it's like to be scared about tornadoes," he says. "We've certainly been more aware of it since."

Spalla remembers the other big one, the 1989 tornado, the one that shredded much of Southeast Huntsville. Her husband picked up their daughter from school early that day, shortly before the tornado hit Jones Valley School. Spalla heard the fatalities at the school reported on the radio before she learned her daughter was safe. "It's something you don't forget," she says.

Consequently, few call foul when the hotly competitive Huntsville TV stations breathlessly pre-empt programs with a tornado warning. It's a matter of community safety, after all.

But in television these days weather is also good business.

"Weather is just so interesting to people," says Mackey Morris of Frank Magid & Associates, one of the country's leading consulting companies for local news programming and promotion. Magid, based in tiny Marion, Iowa, has clients in almost all of the 150 major television markets. In Huntsville, that station is WAAY, and it gets the same advice on weather coverage as all Magid clients.

"It's an interesting thing that dictates people's lives," Morris says. "Go to Chicago and get in a cab, and what's one of the first things you're going to say to that Russian-born taxi driver?"

What's also similar most everywhere is the technology tussle. All across America there are promos touting First Alert, Double Doppler, Storm Tracker, No-One-Else-Has-It Weather Centers. Although Morris says people won't tolerate being lied to about technology, they will stomach a little showboating.

"Some of it is bells and whistles," he says. "But for years, it's obvious that people appreciate the promotion. They expect it."

Expect is soon from WAFF, which has been a quiet and distant third for years and doesn't plan to be either much longer.

"The other stations have their promotions in high gear," general manager Pimental says. "We know we're going to have to do the same. We can't whisper. We're going to have to do some yelling. But we're going to keep it in perspective."

What's next for the two front-runners? Smith says WAAY is toning down its self-promotion efforts and running commercials that softly accentuate his station's strengths, rather than shout comparisons with the competition.

He saves such comparisons for his office. He wonders aloud, for instance, whether rival WHNT weatherman Dan Satterfield hasn't developed a Doppler trigger finger, alarming viewers with premature storm warnings. "We're not going to play that same game," he declares. "Because I believe it ends up hurting you."

Linda Spalla, meanwhile, sees no problem with what WHNT is doing. "We have literally surged ahead," she says.